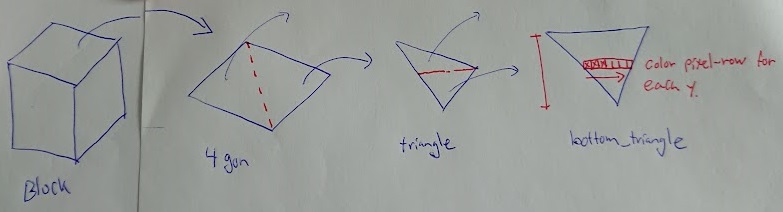

- Code everything from scratch in C/C++, no external libraries

- Over 100 puzzle levels

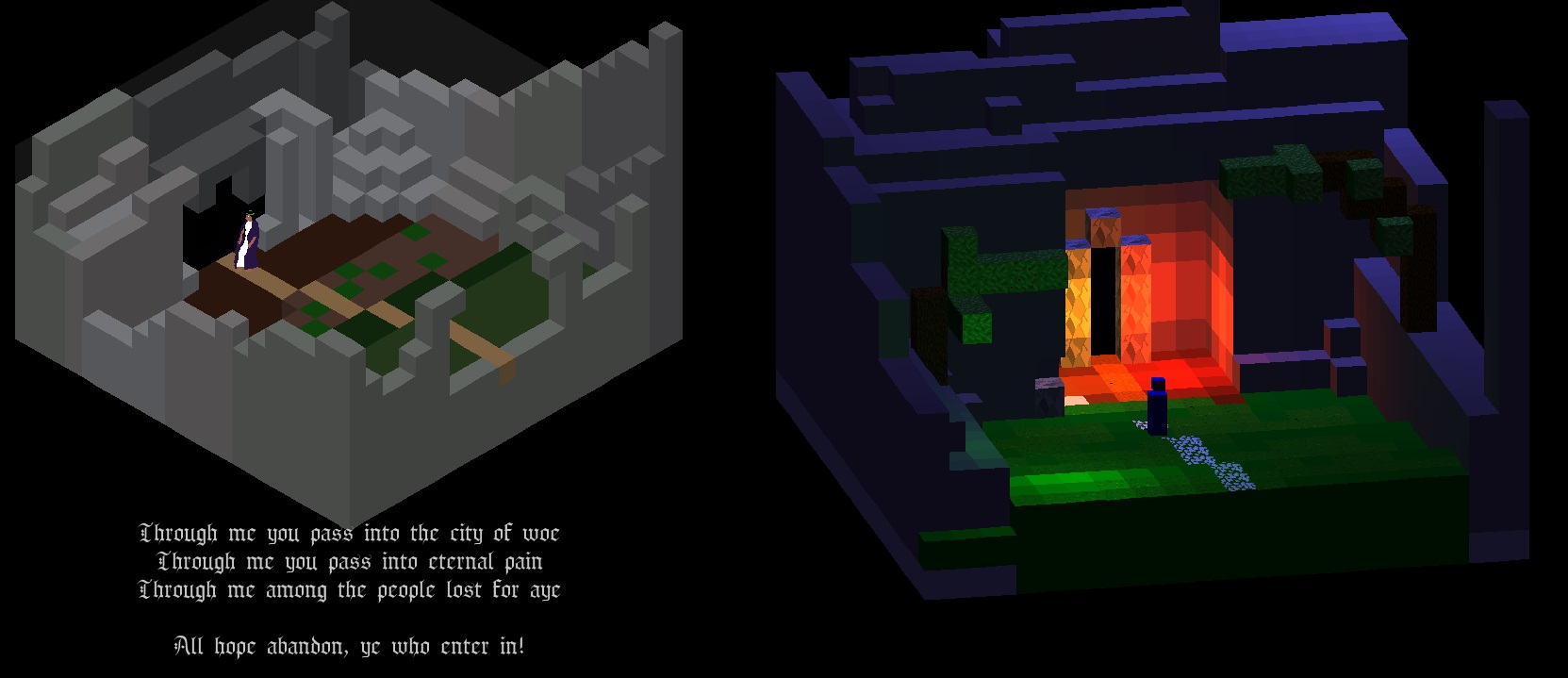

- Serious tone to the presentation

- Each puzzle should bring something new, no repeating puzzles

- Puzzles shouldn't require massive trial and error to solve, the player should be able to find the idea to solve them

- The setting of the levels (not the puzzles themselves) should follow Dante's poem pretty closely

- Each circle of hell should bring some new mechanic

- Each circle should have its unique color scheme, lighting scheme, textures

- Each circle ends with a "boss puzzle" requiring mastery of the mechanic

- Avoid puzzles requireing timing or fast inputs.

- Minimal UI

- Over 60fps on an average CPU

- Playable without instruction

- Playable with only keyboard or mouse

- All level creation from an ingame editor

- Coherent menu-system with many configurable options

- Quotes from Inferno before every level

- Colorize art for each section of the game

- Steam integration with achievements